In competition players don’t run 10 metres straight ahead, make a 90 degree cut and run exactly 5 metres before reversing direction back to the starting point. Instead, they must react to the actions and positions of opponents, teammates, and the ball. Consequently, preplanned agility training has received a bit of a bad wrap lately. Some coaches are shying away from it completely.

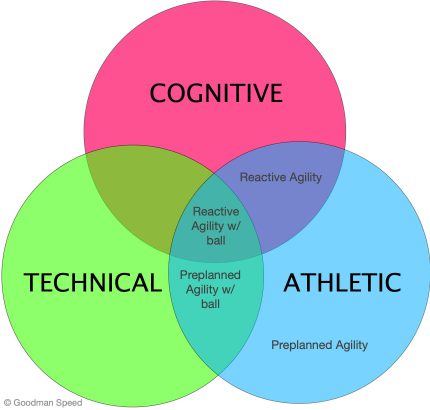

This is a mistake. Reactive agility is not more important than preplanned. They are both crucial, and equally important for sporting success. It is vital to recognize that they are two separate things: Reacting appropriately to the right stimulus and doing so quickly is an expression of cognitive speed. Producing or changing movement is athletic speed. (And if you add a ball into the mix, manipulating it introduces a third component —technical speed.) They are independent attributes that are required in various combinations in sport.

None are more relevant than the others. All are necessary for sporting success and each one is able to distinguish between players at different levels of competitive play.1-4

That is, more successful players are faster cognitively, technically, and athletically compared to less successful players in their sport. This is not always the case with other physical attributes like strength, flexibility, endurance, anthropometry, or FMS score. 1,3,5-8

Therefore, to improve competitive performance, all three facets of agility (cognitive, technical, athletic) must be trained… maybe just not all together.

As coaches, S&C coaches, or physiotherapists, we know that we shouldn’t throw too much at our players at once. This is because they will not improve —and may even regress— when the training demands are inappropriately high. Of course, this concept also applies to agility training. With complex drills that simultaneously challenge cognitive, technical and athletic abilities, players are more likely to become overwhelmed and not receive any positive benefit from the training.

Unless each facet is perfectly tuned, the outcomes from combined drills are unlikely to be what you are aiming for. By attempting to train all three facets at once, either the weakest will not be getting the detailed attention that is required to ameliorate it; or the other two facets are not being challenged enough warrant inclusion and are just distracting from the task at hand.

By instead selecting and designing drills that deliberately focus on their weak link(s)9 —regardless of whether it is cognitive, technical or athletic speed— players can achieve greater and more rapid improvements in game performance with less invested time and energy in practice.

Preplanned agility should be your choice for teaching optimal biomechanics and developing the power necessary for producing athletic speed. To make it more realistic, and for better carry-over to competition, the distances and angles can be varied somewhat between reps. However, the emphasis must remain on the quality and intensity of movement.

Adding a reactive (cognitive) component to agility drills only makes sense when the players can move optimally and explosively. Until that point, it is best to train cognitive speed without requiring athletic movements. Simple pointing or gaze fixations should be used instead of moving the whole body.

In a similar vein, technical components should first be targeted in isolation, and only incorporated into agility drills that involve movements (athletic speed) at which the players are already adept.

The Goodman Speed specialty courses cover each respective facet in-depth over multiple days of classroom and field/court instruction. We’ll also explore some of these in future Insights, so stay tuned.

-CG

1 Arazi, H. et al. (2016) “Relationship between anthropometric, physiological and physical characteristics with success of female taekwondo athletes.” Turkish Journal of Sport and Exercise 18.2: 69-75

2 Rosch, D. et al. (2000) “Assessment and evaluation of football performance.” The American journal of sports medicine 28.5_suppl: 29-39

3 Sell, KM. et al. (2018) “Comparison of physical fitness parameters for starters vs. nonstarters in an NCAA Division I men’s lacrosse team.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 32.11 (2018): 3160-3168.

4 Sheppard, JM. et al. (2006) “An evaluation of a new test of reactive agility and its relationship to sprint speed and change of direction speed.” Journal of science and medicine in sport 9.4: 342-349.

5 McGill, SM. et al. (2012) “Predicting performance and injury resilience from movement quality and fitness scores in a basketball team over 2 years.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 26(7), 1731-1739.

6 Ramos-Campo, DJ. et al. (2016). “Physical performance of elite and subelite Spanish female futsal players.” Biology of sport, 33(3), 297-304.

7 Ramos, S. (2020) “Differences in maturity, morphological, and fitness attributes between the better-and lower-ranked male and female U-14 Portuguese elite regional basketball teams.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 34(3), 878-887.

8 Rosch, D. et al. (2000). Assessment and evaluation of football performance. The American journal of sports medicine, 28(5_suppl), 29-39.

9 Right now you can probably make a decent guess as to which your players need most, but in the Integration course, you will learn how to accurately determine which really is their weakest link. We also teach you how to determine when to isolate each; as well as which, when, and how to best combine them.